Insights: ASEAN Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform Webinar Series

Background

Fashion is a major industry in the global manufacturing sector, ranking third behind automotive and technology. However, its growth has come with significant environmental costs. Textile and leather production, in particular, are major polluters, generating toxic wastewater and consuming large amounts of energy and water. The rise of fast fashion worsens these issues by promoting fast-turnover, low-quality clothing made from plastic fabrics such as polyester. In developing countries, affordability often comes at the expense of sustainability. To address these issues, holistic approaches promoting sustainable consumption and production are vital, emphasising practices like circular fashion and eco-friendly materials. Educating consumers about sustainable choices is also crucial for the industry’s journey towards sustainability.

Key Takeaways

These key takeaways from the webinar offer a comprehensive overview of the strategies for sustainable consumption and production of fashion industry:

- Economic Importance and Challenges: Textile manufacturing plays a crucial role in economies worldwide, particularly in regions like Southeast Asia. However, the industry’s linear economic model, characterised by take-make-use-waste, leads to environmental degradation and labour rights abuses.

- Textile Industry’s Unsustainable Practices: The textile industry faces significant challenges due to its unsustainable production and consumption patterns resulting in an alarming rates of water consumption and pollution discharge, microplastic pollution, and rapid clothing disposal.

- Need for Systemic and Circular Change: There is a growing consensus on the necessity of systemic and circular change within the fashion industry to shift the consumption patterns, improve industry practices, and invest in infrastructure for waste management.

- Policy Interventions: Government policies and regulations play a crucial role in driving sustainable practices within the fashion industry by promoting sustainable production, consumption, and waste management practices.

- Emergence of Sustainable Fashion Initiatives: The movement towards sustainable fashion initiatives demonstrates the potential for local solutions to contribute to global sustainability goals, highlighting the importance of grassroots efforts in driving change.

- Consumer Awareness and Behaviour Change: Educating consumers about the environmental and social impacts of their clothing choices is essential for driving behaviour change towards sustainable fashion consumption.

- Innovations and Partnerships: Innovative approaches are emerging as solutions to address environmental challenges in the fashion industry through multi-stakeholder partnerships driving systemic change and scaling up sustainable initiatives.

- Challenges and Barriers: Significant challenges and barriers that hamper circular fashion include limited resources for scaling up sustainable initiatives and infrastructure limitations.

- Local and Global Solutions: While global initiatives and policies are essential, local solutions tailored to specific contexts are equally important. Cities and communities play a crucial role in shaping sustainable fashion consumption through initiatives at municipal-level and support regional collaborations to share best practices and resources.

- Holistic Approach to Sustainability: Achieving sustainability in the fashion industry requires a holistic approach that considers environmental, social, and economic factors, including integrating circular principles into production processes, promoting ethical labour practices, and fostering a culture of innovation and collaboration across the industry value chain.

Introduction

Fashion has always been a crucial aspect of human society, influencing trends, lifestyles, and the economy. Currently, the fashion industry ranks as the world’s third-largest manufacturing sector, trailing only behind the automobile and technology sectors. It encompasses various subsectors, including textiles, garments, ready-to-wear, leather, footwear, accessories, beauty, and cosmetics. As the industry expanded rapidly to meet the insatiable demand for new fashions and styles, its environmental footprint also grew significantly across the entire value chain, from material production to disposal.

The textile and leather industries are among the world’s most water-intensive and polluted sectors. The untreated effluents from fabric dyeing and leather processing contain toxic chemicals, heavy metals, and suspended pollutants, and are highly alkaline. Fabric dyeing alone accounts for 20% of global wastewater generation.[1] The combined release of untreated wastewater adversely affects community and human health, as well as the health of plants, animals, and ecosystems. These industries also consume a significant amount of energy, necessitating high-temperature water to facilitate the absorption of chemicals and dyes in the materials.

Furthermore, the fast fashion business model exacerbates the environmental and social impacts of the fashion industry through the rapid production, consumption, and disposal of low-quality products made by inexpensive labour. These products, often made from synthetic fabrics like polyester, are cheap but have a considerable environmental cost. Synthetic fibres, derived from fossil fuels, require approximately 1.3 billion barrels of oil annually and contribute to half a million tons of microplastics from washing and cleaning garments to enter our oceans each year.[2] An estimated 87% of all produced fibres end up in landfills or are incinerated, amounting to 92 million tons of textile waste annually, predominantly from fast fashion.[3]

Moreover, packaging which made fashion products distribution possible, are creating additional environmental burden. The overuse and mismanagement of plastic packaging are especially problematic due to their long lifecycle and remaining in our environment through multi-generations. The cosmetic industry, in particular, faces packaging waste issues. About 95% of all cosmetic packaging, predominantly plastic, is discarded after use, totalling around 114 billion pieces annually.[4]

In ASEAN and other developing countries, beauty products are often sold in sachets, providing affordable options to low-income consumers but exacerbating environmental issues due to improper waste management. These issues include fossil fuel consumption and carbon emissions from packaging production and the water-intensive nature of rinse-off cosmetics for body, hair, and skin care.

Recognising the interconnectivity of the sectors within the fashion industry, holistic approaches that promote sustainable consumption and production (SCP) strategies and a circular economy involving multiple stakeholders are essential for transformation.

Sustainable production practices, such as circular fashion, using eco-friendly materials, and leveraging technology and innovation, can reduce the environmental footprint of each fashion item. Consumers also need to be educated and encouraged to adopt sustainable consumption habits to complete the fashion industry’s cycle towards sustainability.

The 1.5-hour webinar “Circular Fashion: Sustainable Consumption and Production Across Textiles, Leather, and Cosmetics,” hosted by the ASEAN Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform (ACESP) and co-hosted by the EU SWITCH-Asia Policy Support Component, showcased holistic circular approaches within the fashion industry from producer, consumer, policy, innovation, and partnership perspectives.

The event began with a welcome note and an overview of the ASEAN Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform, highlighting its role in consolidating and facilitating regional efforts. Elodie Maria-Sube, Key Expert on EU policy development and partnership building at the SWITCH-Asia Policy Support Component, presented a background on the environmental footprint of the fashion industry along with sharing exemplary fashion and textile projects funded by the EU SWITCH-Asia.

Fashion industry practitioners came together to discuss how fashion does not have to always equate to dirty and unsustainable but rather can be done sustainably through SCP and circular strategies; creating awareness for consumer behavioural change; and multi-stakeholder innovation and systemic change.

This expert discussion culminated in five key questions that need addressing:

- How can the textile industry balance economic importance with the need for responsible practices, particularly in regions like Southeast Asia?

- What policy interventions are most effective in driving systemic change towards circular fashion?

- How can consumer awareness and behaviour change be effectively promoted to encourage slow fashion consumption?

- What role do innovations and partnerships play in addressing the challenges and barriers to sustainable fashion?

- How can local initiatives contribute to global sustainability goals in the fashion industry?

ASEAN Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform

Anthony Pramualratana and Treesuvit (David) Arriyavat, Deputy Director and Project Manager respectively at the ASEAN Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform (ACESP) gave a welcome note on the various aspects of circular fashion, including sustainable materials and production processes, design in extending garment life spans, the rise of second-hand clothing, and rental models as alternatives to the traditional consumption and production patterns within ASEAN region. Furthermore, they introduced the ASEAN Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform, a regional facility supporting ASEAN member states to transition to a circular economy by providing access to good SCP and circular economy strategies, facilitating stakeholder engagement, and organising events such as the Annual Circular Economy Conference for the ASEAN Region, or setting up engagement groups consisting of circular economy leaders from various sectors in the region.

Understanding Fashion’s Footprint

In this session, Elodie Maria-Sube provided an overview of the footprint of the textile sector globally, in Asia, and in the EU. Textiles are essential to human beings not only because clothing is crucial for human welfare, but also because the industry provides high levels of employment and generates $1.5 trillion in revenue. Textile production is far from sustainable, consuming 215 trillion liters of water per year and contributing to 9% of annual microplastic losses to the oceans. The unsustainable consumption has exacerbated the crisis by consuming and discarding items at a much faster rate, using items 36% less before discarding them compared to 15 years ago. Every second, a truckload of clothing ends up in landfills or is incinerated. This linear system leaves economic opportunities untapped, puts pressure on resources, pollutes and degrades the natural environment and its ecosystems, and creates significant negative societal impacts at local, regional, and global scales.

The Fashion Sustainability Report 2021: Focus on Change & Southeast Asia reported that textile manufacturing plays an important economic role in Southeast Asia. Cambodia’s economy is largely reliant on its garment industry, which caters to 200 international brands and represents 80% of its exports in value. Moreover, 90% of its garment workers are women. Vietnam’s textile industry employs more than 2 million workers, and its textile and clothing exports comprise 15% of the country’s GDP. Indonesia’s textile exports are worth US$12.7 billion. The textile and garment economic models in Southeast Asia are very linear—where we take, make, use, and waste—so environmental degradation is commonplace. Additionally, labour and human rights abuses are often reported in these industries.

It was agreed and reported in the Sustainability and Circularity in the Textile Value Chain: A Global Roadmap that systemic and circular changes are much needed for the industry. The report identified three interconnected priorities to deliver this change: shifting consumption patterns, improving practices, and investing in infrastructure. These priorities are interconnected and need to be addressed as part of a coordinated approach involving all value chain actors. It is not just about consumers, businesses, or infrastructure alone, but rather all three elements coming together. Consumers should decide to buy and consume less textile and use them longer. Businesses should produce better quality textiles and garments that last longer and are perhaps made out of recycled materials. More infrastructure is also needed for properly discarding textile waste. These are all parts of an interconnected and circular chain.

The EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles, published in 2022, works towards a shared goal for sustainable fashion by leading to the adoption of many laws at the EU level in 2023. The Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation creates a framework to set ecodesign requirements for products, including textiles are to be made from recycled materials and to be made to last longer. The Empowering Consumers in the Green Transition Directive and Green Claims Directive aim to tackle greenwashing. The Waste Shipment Regulation restricts the export of textile waste to other countries. Also in 2023, the Commission proposed a revision to the Waste Framework Directive to introduce mandatory Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes for textile waste management in all EU States.

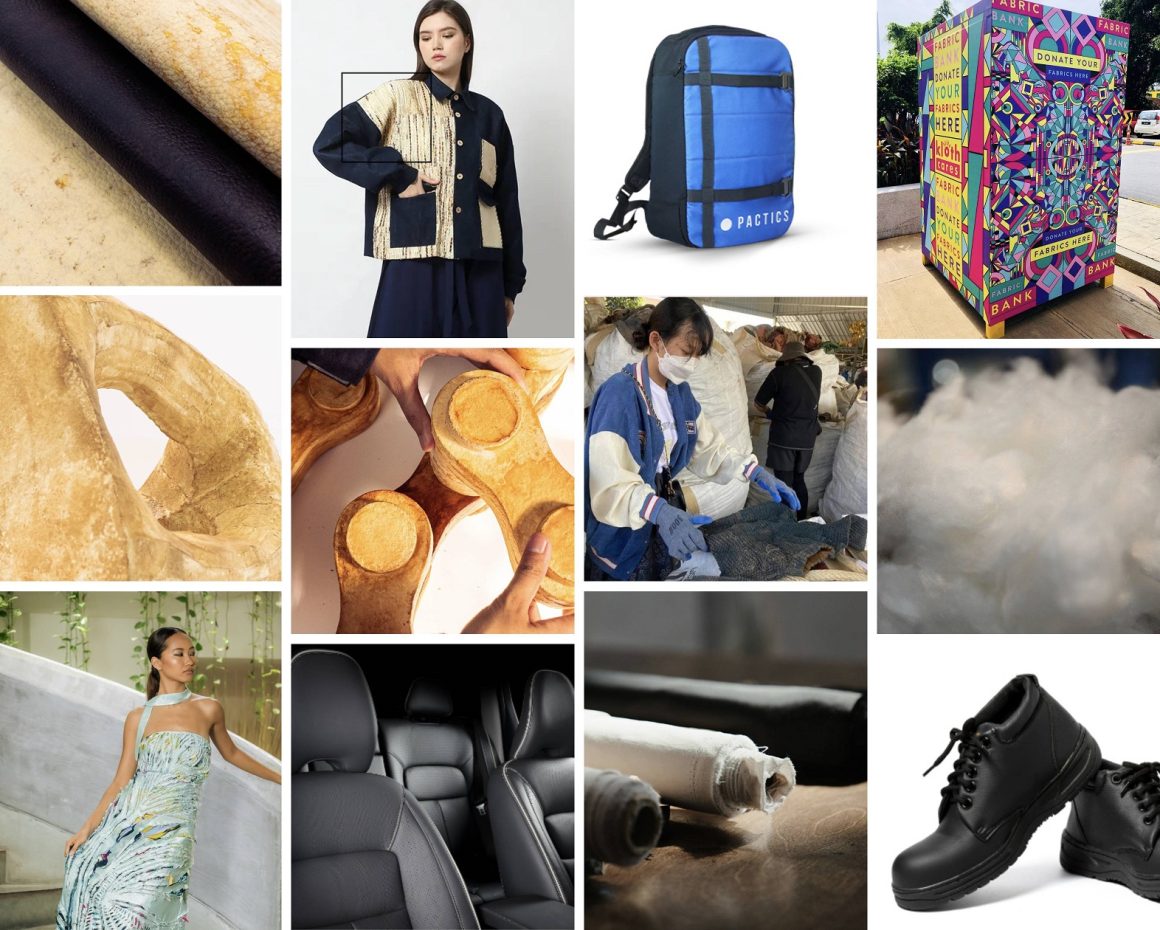

Fashion is a fast-growing market in ASEAN, especially in Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore, valued beyond US$ 50 billion. However, sustainable fashion is still happening on a small scale and more locally, yet it still holds great economic potential. There are many excellent bottom-up initiatives to encourage reuse in ASEAN, such as the Zero Waste Indonesia, Fashion Pulpit in Singapore, and The Swap Project in Malaysia. The EU SWITCH-Asia funded 21 textile and leather projects promoting SCP, five of which are in ASEAN, with one project remaining ongoing by the end of this year. Some of the exemplary projects include Switch Garment from Cambodia, SMART Myanmar I & II, Handwoven Eco-textiles in Indonesia and the Philippines, the Clean Batik Initiative in Indonesia and Malaysia, and identified business cases such as the BANIG – Basey Association for Native Industry Growth Inc. in the Philippines and PACTICSin Cambodia.

Panel Discussion: Sustainable Consumption and Production Strategies for Circular Fashion

Elodie Maria-Sube moderated the session on strategies to help move the fashion industry towards circularity and began with the definition of circular fashion and its important elements.

Adi Reza, Founder of Mycotech Lab (MYCL), explained that sustainable biomaterials made from mushroom mycelium are at the core of MYCL’s circular business strategy. Its leather-like material is made from agricultural waste, which is abundant in Southeast Asia, underutilized, and often ends up being burned or left on the land. Converting this crop waste into something with added value using mushroom mycelium technology prevents the linear model from taking place and circulates materials into more valuable products that are eco-friendly and create benefits for society. MYCL works with several marginalized farmers in its supply chain to acquire mycelium to create these innovative products. On the other side of the value chain, it collaborates with artisan leather product designers and manufacturers, offering them access to sustainable materials that are normally difficult to acquire and may only be possible for large companies. This circular and inclusive model allows small and medium enterprises to produce and sell sustainable, high-quality products.

There are three main drivers to this circular and inclusive model: environmental consciousness, ethical considerations, and innovations. There is a growing awareness of the environmental impact of the fashion industry and a growing demand for sustainable fashion from customers. Additionally, there are increased concerns for human and labour rights, as well as animal welfare in the industry that are influencing consumer decisions. Lastly, advancements in technology for sustainable materials offer consumers high-quality and eco-friendly alternatives that behave like leather with the same performance—durability, flexibility, heat resistance, and moisture resistance—but without using plastics or harmful chemicals in the process.

The biggest cost barrier in scaling up for a young start-up with limited resources is the Free-of-Charge (FOC) for demonstration practices done between B2B. Small and medium enterprises who are eager to create change but are having difficulties accessing sustainable materials face a similar cost barrier. Sometimes R&D is required to bring a new product to market, and this too can be challenging with limited resources. Therefore, these barriers can make it more difficult for products to be accessible to end-consumers, to purchase sustainable fashion, and to become mainstream products in the market.

Arjen Laan, CEO at PACTICS, elaborated that the company uses recycled polyester and employs waterless dyeing techniques. More than half of its portfolio is now recycled, and they hope to reach 90% in a couple of years. Arjen clarified that PACTICS does not yet consider itself a 100% circular economy company, but it strives to do its best through several initiatives, acknowledging the importance of having ambition and consistency to continue the long journey towards circularity and inclusion. At its factory, there is a large three-step programme on waste reduction, using recycled materials, and reusing waste.

The lack of infrastructure poses challenges. Cambodia only has a finished goods manufacturing industry, where raw materials are made into other products for the market. There are no mills or processing industries, resulting in extreme difficulties in reusing waste. On the other hand, taxes and regulations are also a large barrier in preventing waste from being utilized. In most cases, waste must be incinerated due to enforcement, or penalties would be imposed. These regulations, which only allow investing companies to import and export, hamper future development, especially sustainable development on a large scale. At the moment, some experiments on reusing or refabricating certain things are allowed without being penalized.

The intrinsic driver for this persistent journey towards circularity is the amount of post-industrial waste humanity generates. Big containers of products that can no longer be used are shipped off to be incinerated on a regular basis. But these are materials that had never been used before and are now thought to have no other purpose. In truth, these are valuable materials. PACTICS, as a relatively small company, burns around USD 300,000 to 400,000 a year, impacting the environment and economics. There is a drive for an innovative business model to cleverly work to waste less. There is also a driver from consumers who want something new or different. PACTICS made bags from vegan leather. On a small scale, this still works but can be quite difficult to apply on an industrial scale. It will take time, investments, and experience to scale up.

Panel Discussion: Consumer Awareness and Behaviour Change Towards Slow Fashion

Loraine Gatlabayan, Key Expert on SCP awareness raising and regional partnership building at the SWITCH-Asia Policy Support Component, moderated the session on the important role of consumer awareness and behavioural change towards fashion sustainability. She began by emphasizing how awareness and education of consumers are crucial to contributing to and pushing for a greener fashion industry. When consumers learn about the environmental consequences of their clothing choices, they can make smarter decisions, choose sustainable materials, and select brands that align with their values. By doing so, they can buy fewer, higher-quality garments that are then used longer, thereby eliminating the fast fashion throwaway mentality.

Katia Dayan Vladimirova, Founder and Coordinator at the International Research Network on Sustainable Fashion Consumption, has been focusing on fashion for the past 8 years and is now trying to understand how to transform social norms and values towards fashion sustainability. Research in other sectors has shown that awareness of environmental issues or social negative impacts from a supply chain is not enough to convince consumers to buy better. Additionally, simply buying better is not a sufficient solution for moving forward. This is because we cannot “green buy” our way out of the crisis of overproduction and overconsumption. While circularity is a critical central element to the renewal of ecosystems, we also need to combine circularity with sufficiency. Many people are engaging in circularity by reusing, hence, the fashion second-hand market is growing rapidly. However, not all second-hand products are of good quality; they cannot be reused forever. The quality of ultra-fast and fast fashion garments deteriorates over a short period of time. Key data supporting sufficiency is that having fewer, better-quality items has resulted in higher levels of subjective well-being or happiness. This is why people are moving towards having fewer clothes, shoes, and accessories; because living with less but better garments makes them happier.

The reason why fashion is fast today is because efficiency has been increased to a level where it disregards people and the planet. However, slow fashion is returning back to humans and to the environment. In terms of slow fashion initiatives, according to Katia, the most promising angle for scaling is to support initiatives at the municipal or city level, where neighbourhoods and people are involved. The role of cities is crucial in shaping sustainable fashion consumption. Cities have the capacity to support local initiatives and, at the same time, are able to create synergies among different stakeholders needed to work together. The most interesting solutions are the ones that manifest locally and there is no one-size-fits-all approach. They must be culturally specific, such as location, climates, and resource-specific. But there are also possibilities for scaling beyond the city level to regional collaborations and exchanges to learn from and inspire each other.

Sarah Kedah, Co-founder at Klothcircularity, shared the company was founded 11 years ago when circular fashion was unheard of. The team wanted to promote products made from sustainable materials and fibers, but it was very difficult due to the lack of awareness of the problems. Rebranding then occurred to raise awareness of the issue of textile waste, how to keep fabrics from landfills and incinerations, with the 5R philosophies: rethink, reduce, reuse, repurpose, and recycle. Operating in Malaysia and Singapore, people always have the mindset of donating their unwanted clothes and someone will wear them, Sarah explained. The demographics and background are often overlooked; we are multiracial and multicultural, which means everyone has different needs, and one must know their beneficiaries in order to serve their purpose. Cloth recycling boxes are provided and we convey the message that 60% of our clothing can be reused rather than sending it to the landfill. The rest are repurposed into industrial cloths using mechanical separation. Cotton can be shredded into fibers to make home cloths and furnishings. In the future, Klothcircularity strives for technology to turn textiles into textiles.

Reducing and having fewer garments is the way forward, and we always inculcate this to our consumers and audiences, Sarah explained. Social welfare is also important when making consumption decisions, to consider who made your clothes. Klothcircularity engages with women from marginalized communities and offers them employment opportunities to make materials into beautiful products. There are more than a thousand partners and supporters in its network, including governmental organizations, businesses, brands, and event organizers. Other initiatives include government and event green procurement in how to move forward and support environmental and social issues through upcycling merchandise.

Alyssa Erin Kardos Loera, CEO & Creator at ReMade in Cambodia, stressed that 20% of the waste in rivers in Cambodia is textiles, which creates many issues, and few are aware of it. It is important to go beyond education and awareness, towards empowering people with knowledge of the issues surrounding their communities and the journey and circulation of textiles: where they are going, what is being imported, where they end up, and why. An artistic project such as a fashion show can help create awareness of the issues and empower people. The first concern is that textile waste is affecting the rivers and wildlife in the communities, and the second is the lack of Cambodian designers within the Cambodian fashion industry. The ReMade in Cambodia business model involves recovering waste from the rivers and collecting it from communities, then working with young Cambodian designers to upcycle the textile waste into fashion and new products. We started with the arts because it is an accessible means for people to interact, and fashion shows are quite popular.

The current focus is on upscaling the upcycling through a community-focused model, multi-stakeholder partnerships, and promotion through social media. When talking about upscaling, the most important thing is providing more jobs and thus being able to produce more. Communities lost jobs due to factory closures, and the upscaling will be a positive change within the communities. There is also a need for a holistic approach that involves youth. The average age in Cambodia is 27, and oftentimes youth are never included in these discussions. More importantly, fashion and textile waste management are often separated. It is important to approach both together and make it something interesting through engagement with people artistically and holistically, looking at issues and building a sustainable future together.

Panel Discussion: Driving Systemic Change in the Fashion Industry Innovations and Partnerships

Zinaida Fadeeva, Team Leader, SWITCH-Asia Policy Support Component moderated the session on how large corporates can pave the way towards circularity and drive systemic change.

Djemi Gunawan, Head of Circularity at Asia Pacific Rayon (APR), explained that Asia Pacific Rayon is a bio-based product manufacturer in Riau Province, Indonesia. They are Asia’s first manufacturing facility vertically integrated from plantations to fiber. APR is guided by state-binding principles. Everything the company does must be good for the community, which in turn will be good for the company. This guiding principle keeps APR risk-free without challenges in applying circularity to their business model. All international and national policies are followed. They also assist stakeholders in becoming more circular. Market regulation enforcement plays a significant part in the company’s direction and practices. Any standards that benefit the environment, community, climate, and country will be followed, for instance, the EU Circular Economy Action Plan has become the guideline.

APR strives to operate sustainably and circularly through innovation to secure their sustainable growth. Currently, an initiative called Urban Textile Cycling Path in Singapore is being researched and designed by a local partner as a pilot project. Singapore was chosen for this pilot project due to its small population number. If it works here, it should be applicable in other cities. This initiative aims to close the loop by collecting waste, sorting waste, recycling, and sending it to the plant to be mixed with virgin pulp. APR also has its own R&D center with highly qualified technicians working on optimizing the process, testing various textile wastes, and finding ways to integrate 20% of textile waste into their Viscose Staple Fiber (VSF). This process was approved to be patented in early 2023.

APR engages with many stakeholders such as associations, retailers, and garment manufacturers. Most notably are the partnerships for the Sustainable Textile Change, consisting of APR and two upstream suppliers, two downstream textile companies, and two NGOs. Sustainable Textile Change is a platform to share experiences and best practices to implement joint actions towards sustainability. APR is also collaborating with one of the biggest fashion retailers in Indonesia to implement textile waste maintenance systems in Indonesia by placing 46 drop boxes in four big cities and setting up logistic infrastructure to collect the waste from the end consumer. The waste is then sent to sorting partners to segregate the waste based on categories of post-consumer waste and check fiber composition in each garment collected and separate all plastic materials from those garments. The idea is to make the value of the waste higher and optimize the end-use of that waste.

Wasin Thumrongsakunvong, Director and General Manager at Interhides PCL (IHL), shared that IHL is one of the largest leather manufacturers in the world. In circularity, consideration of where the raw material comes from is essential. Beyond the manufacturing, leather is generated from the waste of the meat business, whether from cows, pigs, or sheep. Leather is then an upcycled by-product from turning the supposed waste into something that is usable and value-added. IHL works with many stakeholders around the world which raise meat such as in the United States, Argentina, Brazil, and Thailand. Especially in Thailand, there are a couple of programmes working with local farmers whose livelihoods depend on selling cows and generate most income from their 9-10 months of effort in raising the cows. When every part of the cows—meat, bone, blood, and hide—has a purpose, then that is true circularity. Leather helps generate another source of stable income for farmers in the meat business.

There are many policies enforcing the leather industry including regulating chemicals, processes, discharges, labour, and more, but IHL always strives to go beyond the enforcing policies and look forward to what could be done to better the planet. Looking beyond the present towards new standards, regulations, and legislation in Thailand and the global market prepares the company for the future. This is what the customers always appreciate. Moreover, IHL’s procurement standard extends responsibilities to suppliers by prohibiting the use of harmful preservatives and ensuring every piece of hide is processed as well as possible so that no piece of leather becomes waste. Every piece of hide and leather is respected and this should be also reflected upon the suppliers as well.

IHL implements philosophy-driven technology and innovation to combat the perception of being a dirty industry. It strives to become a zero-waste company, and at the moment it is at 95% efficiency of zero waste. It is working with its customers for the remaining to achieve 100% efficiency. Most noteworthy technology and innovation at IHL are water recycling and recovering protein from leather scraps for fertilizer and pet foods. It also partners with stakeholders to drive systemic change. For instance, IHL partners with Vivo Barefoot—a shoe brand from London—to support smallholder farmers. The concepts stemmed from the desire to offer economic stability through supporting communities. In most cases, the shoe industry always required perfect looking leather, but in this case, Vivo is willing to overlook perfection for social equality and inclusion, literally speaking. Smallholder farmers do not raise their cows in a pen like large farmers where no trees can scratch their skins. These cows live in nature in the communities, so there tends to be natural defects and inclusions on the cows’ skin. For the past four years, IHL and Vivo support smallholder farmers in Thailand by giving a fair price despite imperfection in the leather.

Moreover, when discussing leather replacement options, there are definitely opportunities in the market. But the questions remain largely on: which term should we use to call these replacements; are we competing with the food source or food security; what environmental impact do these options have; and can these alternatives be produced enough to supply the demands? These questions would have to be answered before upscaling can be done.

- Video recording available here

- Event info at ASEAN Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform and EU SWITCH-Asia

Related readings (from asean.org)

- SUBSTANTIAL TRANSFORMATION CRITERION FOR TEXTILES AND TEXTILE PRODUCTS

- ROADMAP FOR INTEGRATION OF TEXTILES AND APPAREL PRODUCTS SECTOR

- ASEAN Sectoral Integration Protocol for Textiles and Apparel Products

Acknowledgment

This Knowledge Brief was prepared by Dr. Sirasa Kantaratakul, the EU SWITCH-Asia Policy Support Component (PSC) and the ASEAN Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform. The information and contents in this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.